Rousseau has much to say about his career as a composer, something of which I had no idea before reading this book. The second part is less striking, sometimes dull, but still full of interesting episodes. Much of the first book is simply prolonged descriptions of all the women he’s had anything to do with. He begins by describing the erotic pleasure he derived from being spanked by his nanny, relates a few homosexual encounters (undesired on his part), and frequently mentions masturbation. Even more surprising is how frankly sexual is Rousseau’s story. Like any modern self-psychoanalyzer, Rousseau traces his personality to formative events in his childhood-quite unusual at the time, I believe.

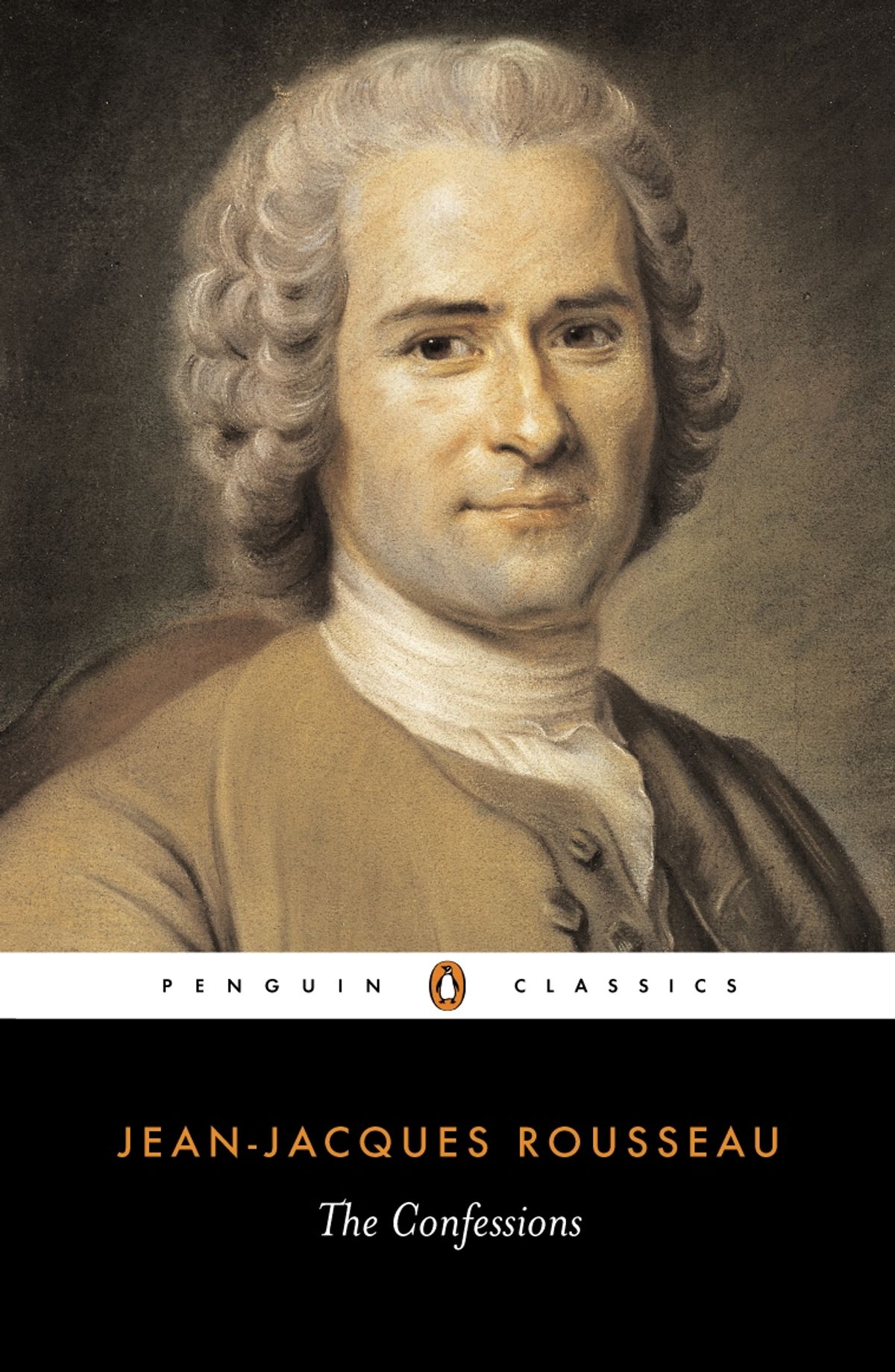

For my part, the first is far better, and far more original. Rousseau’s Confessions is really two distinct works, the first covering his childhood to his early adulthood, the second up to age fifty-three.

This book has found nothing if not imitators.

I suppose this sort of boastful exaggeration shouldn’t count for much after all, Milton began Paradise Lost by saying he was attempting “Things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme.” Nevertheless, the second part of Rousseau’s assertion, that his enterprise would “find no imitator,” is even more indisputably false than the first one. Teresa, Benvenuto Cellini, and Montaigne. Augustine’s famous autobiography, which shares the same name and ignore the works of St. Rousseau, prone to hyperbole, boldly asserts that his autobiography is without precedent. This book begins with a falsehood and only escalates from there. There are times when I am so unlike myself that I could be taken for someone else of an entirely opposite character. Running the (Full) M… on The Madrid Half-Marathon 2023: New Year… on In the Heat: Elche & …Īlicante & the I… on Summertime in Andalucía: Jerez…Īlicante & the I… on The Monastery of El Escor…

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)